Downtown Presbyterian Church Forum, 9/22/2019

Last week I proposed how Rabbi Heschel’s sacred humanism might serve us as a model for faith and behavior.

- He reminds us that all humans have dignity: we are the worldly images of God. We have aspects of divinity; others do also.

- He reminds us that God cares what we do – we might run or deny (we might elevate our human sensibilities above God’s), but we cannot hide from God’s loving search for us. God is the God of the prophets, a God of pathos.

- And Heschel reminds us that along with Godly peace, there is work to be done. The Torah for Jews and the covenant of Jesus are gifts to guide the making of a world that includes God’s vision for mankind. Those gifts are at odds with human proclivities to regard human concepts and human needs above spiritual ones. A God of pathos, a God of concern has also given us choice and freedom – what are we going to do, what are we called to do to build a world of justice and compassion? What we do matters, not only to each other, but also to God.

- That is sacred humanism at work.

This week I will try to lead us into Heschel’s mysticism: how he articulates a position for knowing beyond reasoning, having faith without proof, of living a pious life out of humility at the “tragic insufficiency of human faith.” It begins with and relies on a sense of wonder and radical amazement at our being here at all. His challenge and invitation are to imagine a world where answering human needs is not the only goal.

Dr. Heschel’s search begins with “depth theology” – a search for the sources of one’s beliefs. It is also up to us to search for ourselves – to build our lives as if they were our works of art. At basis there is a leap of faith needed – toward God-centeredness as the source of meaning behind and within our being here and being together.

Even after finding one’s faith (or finding a place toward which we can make a leap of faith), it is always a challenge to maintain the sources of faith. Religions provide creeds, rituals and beliefs to structure faithful actions – up to date religions need to provide up to date answers to the originating questions of depth theology. But, having traditional practices helps – they provide us with a broader awareness of time and belonging. Rabbi Heschel said that his practices of Judaism helped him maintain awareness of God amidst the strain, chaos and lack of truth that surrounded him. Ritual is needed; heart is needed; they both are needed. I will touch on his descriptions of the role and meaning of prayer, the role and meaning of Sabbath, and the nature of a God of the prophets: these I feel will enrich how we see our Christian traditions also.

We will see next week how Heschel’s faith and words can help us to re-assess conventional reality. He warned in 1944 and 1963 about the dangers inherent in complacency, mendacity, callousness and despair – human tendencies that need spiritual and religious energies to resist.

How do we open up ourselves more and more to awareness of an underlying sacredness of being? How do we peel away layers of habit and concept to intuit the presence of the sacred?

“Religion declined not because it was refuted, but because it became irrelevant, dull, oppressive, insipid. When faith is completely replaced by creed, worship by discipline, love by habit; when the crisis of today is ignored because of the splendor of the past; when faith becomes an heirloom rather than a living fountain; when religion speaks only in the name of authority rather than with a voice of compassion – its message becomes meaningless.”

How do we re-discover faith, love, compassion? In this modern age (after Auschwitz and Hiroshima as it were. Also after 9/11 and Sandy Hook …), questions of depth theology can no longer be “conceptual questions” only, ones that are abstract, detached, intellectual. (They are not questions about the nature of God.) Questions have to be “situational questions”: what do we do with “this one wild and precious life” we have? Modern religious questions ask for involvement – and such questioning requires application not only of our rational and conceptual faculties, but also our abilities to experience awe and concern. Not only “what is the good?” but “what is required of you?” The spiritual faculties needed to answer situational questions, Heschel insists, need attention: we need to appreciate them and we have to cultivate them.

But to appreciate the asking of questions, one first has to ask oneself: do I still have a capacity for wonder?

Facing the sky, living in nature, loving at home – are these wondrous or routine? Do we see them as mundane or miraculous? Of course, we have “explanations” for the phenomena we encounter. And it is true that human technology and artistry can create artificial experiences to move us. But does that mean that we “understand” what creates experience? Heschel of course did not have the realities of 21st century technology to deal with. We see the order in the universe even more clearly due to scientific advances, particularly in physics and neurobiology. Religion has been accused of defending a “God of the gaps” – a slowly shrinking realm of knowledge not explained by science: that God provides answers only when science does not. I am not sure Heschel sees the existence of mystery as the proof of God. He first of all and above all marvels at the existence of our capacity for wonder – that we have a curiosity not only for explanation, but also for order and truth and goodness. “The way to truth is an act of reason; the love of truth is an act of the spirit.” When we see the stars, do we only see our human explanations? What do you do with the sense of awe?

Heschel I think is concerned that humanity does not look beyond its areas of mastery. “Man has indeed become primarily a tool-making animal, and the world is now a gigantic tool box for the satisfaction of his needs.” (GSM, 34) “Dazzled by the brilliant achievements of the intellect in science and technique, we have not only become convinced that we are the masters of the earth; we have become convinced that our needs and interests are the ultimate standard of what is right and wrong.” (GSM 35) In other words, the anxiety and reverence and humility of confronting Mystery can be off-putting, to the point that we don’t ask questions about we can’t answer. Religion however sticks with the tough questions: how is this possible? What are we supposed to do with this wonder? How should we act in response? They are not meant to be explanatory answers – they are answers about our responsibilities.

Heschel warned also “there is another ecumenical movement, worldwide in extent and influence: nihilism.” Faith would wonder if there is Something Else beyond reason and measurement to explain or guide our actions. Nihilism might take for granted that what we know is all that matters; or that any ideas and explanations are adequate or equivalent; or that physical laws will eventually explain biology and culture. There is no purpose, only chance, at best created by a disinterested clockwork God. It doesn’t matter what I do and you do; just do it.

Heschel says otherwise: “There is only one way to wisdom: awe. Forfeit your sense of awe, let your conceit diminish your ability to revere, and the universe becomes a marketplace for you.” He recommends an attitude of radical amazement: never dim wonder with indifference. Ultimately it asks for a leap of faith to have this faith. But it creates a world in which one is no longer alone.

[Ketamine story?]

So … if we remain open to questions about how it is that we are here … the questions become situational: what do you do, what do I do with the time and existence that we have? Heschel admits that it is possible and tempting to shrink away from the questions being asked of us. Avoiding these questions, particularly when prosperity and environment provide distractions, can produce indifference to evil and callousness to suffering. One becomes self-satisfied: easy explanations are good enough; ideas to live by need only involve oneself; we are alone and so what? Is that what we want?

He can imagine: “The world in which we live is a vast cage within a maze, high as our mind, wide as our power of will, long as our life span … Those who have never reached the rails or seen what is beyond the cage know of no freedom to dream of and are willing to rise and fight for civilizations that come and go and sink into the abyss of oblivion … [They] prefer to live on the sumptuous, dainty diet within the cage rather than look for an exit to the maze in order to search for freedom in the darkness of the undisclosed.”

At some point, when we maintain a capacity for amazement, spiritual insight can strike, like a thunderbolt, “Apathy turns to splendor unawares. The ineffable has shuddered itself into the soul. … Not an emotion, a stir within us, but a power, a marvel beyond us, tearing the world apart.” (MNA 78) Heschel suspects that everyone has been “shaken for an instant by the eternal.” But how do we preserve the sense of wonder and meaning?

Heschel says prayer and Sabbath are means to do so. These acts are opportunities for reacquainting oneself with God. They are valuable practices to be trained and used. And we can seek understanding of the image of God that the prophets of Israel portrayed: this is the God of pathos, inconvenient at times, but never distant; absent only when he is not sought.

Such a God is more than “ground of being” that Tillich proposes: “Ground of being causes me no harm. Let there be a ground of being, doesn’t cause me any harm, and I’m ready to accept it. It’s meaningless … Isn’t there a God who is above the ground? Maybe God is the source of qualms and of disturbing my conscience. Maybe God is a God of demands. Yes, this is God, not the ground of being.”

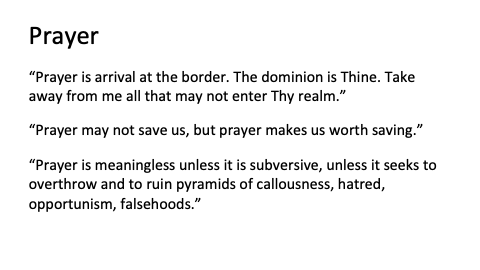

Private prayer is an act of great personal importance to Rabbi Heschel. It is a means to restore a relationship of honesty before God, to listen for God’s purposes for us. “Prayer is arrival at the border. The dominion is Thine. Take away from me all that may not enter Thy realm.”

“We do not step out of the world when we pray; we merely see the world in a different setting.”

“All things have a home: the bird has a nest, the fox has a hole, the bee has a hive. A soul without prayer is a soul without a home. … How marvelous is my home. I enter as a suppliant and emerge as a witness; I enter as a stranger and emerge as next of kin.” Prayer is a way of re-connecting to God.

“Prayer may not save us, but prayer makes us worth saving.”

“Prayer is meaningless unless it is subversive, unless it seeks to overthrow and to ruin pyramids of callousness, hatred, opportunism, falsehoods.” (MGSA, 262)

It is not meant to make requests. Prayer re-orders our priorities and perspectives.

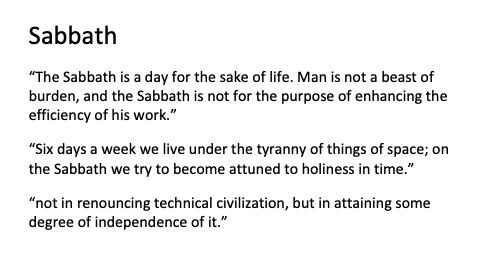

Similarly for the Sabbath, Heschel says this is not an archaic practice out of step with modernity. It is not an exercise in social bonding and communal support. Sabbath is not as a time of rest, to prepare one for the rest of the week. “The Sabbath is a day for the sake of life. Man is not a beast of burden, and the Sabbath is not for the purpose of enhancing the efficiency of his work.” Rather, the Sabbath is a means to survive civilization, to remain free of the material world.

Humanity lives in space primarily, conquers space, uses it. Heschel’s masterful view is that the infatuation with things (objects that occupy space) results in “blindness to all reality that fails to identify itself as a thing.” So, the Sabbath is created to honor Time, not Space. And in honoring Time – when we set aside time to notice, we give ourselves opportunity again to wonder and revere. Jews share with Christians and Muslims the setting aside of a Sabbath time. But for Jews, the sanctification of time is paramount. Not objects, not cathedrals – but it is time for observance that is holy. In Creation, Heschel notes, the works of the first six days were all regarded as “good” but the first holy item was the Sabbath: “And God blessed the seventh day and made it holy.” Sabbath was the culmination of Creation.

“Six days a week we live under the tyranny of things of space; on the Sabbath we try to become attuned to holiness in time.”

On the Sabbath, on the day of holiness, it then is possible to learn how to live without the gifts of technology. Heschel felt this would be an excellent awareness: “not … in renouncing technical civilization, but in attaining some degree of independence of it.” How to have things, but not have to have them. In its ideal, Sabbath is set aside to be free of money and social conditions, free of the toil of work, and also from the toil of emotions and sadness. It is meant to be a day of praise and harmony, a reminder of how God and nature should co-exist. Sabbath can be setting aside time to make us aware of heaven.

“Space is not the ultimate form of reality.” Sabbath and prayer remind us to make time for reflection and connection. “It takes three things to attain a sense of significant being: God, A Soul and a Moment. And the three are always there.”

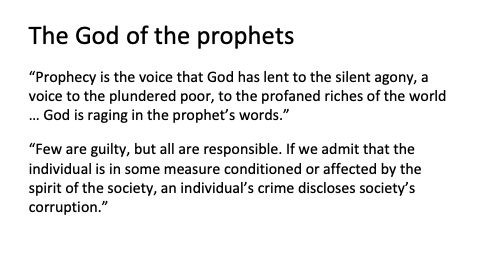

Finally, let me elaborate on the God of pathos whom the prophets declared. The prophets were horrified at injustice and callousness. They did not speak out of personal enlightenment – they always spoke for God: “thus says the Lord.” “Prophecy is the voice that God has lent to the silent agony, a voice to the plundered poor, to the profaned riches of the world. … God is raging in the prophet’s words.” Prophets are unimpressed with human grandeur (wealth, wisdom, might) – especially if it is built on injustice and human suffering. Israel was God’s chosen people, and thus represented an example to all peoples. Israel was meant to live as a moral society. “Few are guilty, but all are responsible. If we admit that the individual is in some measure conditioned or affected by the spirit of the society, an individual’s crime discloses society’s corruption.” And the greatest corruption is the coalition of callousness and authority. The prophets expressed God’s outrage at that.

The prophet speaks for God as a concerned Being. Behind and within the exhortations and chastisements there is always concern. The prophet’s concern (God’s concern) is that might is not right. The ancient world, and perhaps the modern one, glorified might. The prophets regarded reliance on might as evil.

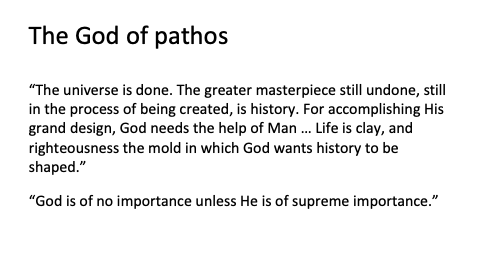

History for the prophets is where mankind demonstrates its use of power: in God’s favor or in favor of human concerns. The Bible, according to Heschel, is a history of God’s search for mankind to live rightly (by the will of God) – and mankind’s defiance in favor of power, injustice, greed and callousness. But whenever there was repentance, there was God prepared to welcome back the wayward community. God is available when pride is relinquished. “The universe is done. The greater masterpiece still undone, still in the process of being created, is history. For accomplishing His grand design, God needs the help of Man. … Life is clay, and righteousness the mold in which God wants history to be shaped.”

Righteousness and Justice – these values and concerns are the gift of the God of the prophets to humanity. God has a plan, and God needs humans to carry out the plan in partnership.

The Jewish God, great and mighty Creator of all, still and always remains concerned about the deeds (motivated by the thoughts and impulses) of each organism called human – seemingly insignificant, each has worth and purpose. The Jewish God is the most moved mover. And we therefore can hope to contribute to the building of goodness in the world when we seek understanding of God’s ways.

When God seems absent, according to Heschel’s mode of belief, it is not because of disinterest, retribution, or “death of God.” God seems absent when mankind neglects to maintain a relationship with God, when individuals and cultures refuse to seek God-understanding. Trouble and tragedy occur when humanity imagines it does not need guidance; imagines it can rely on its own powers, skills, reasons and will.

“God is either of no importance unless He is of supreme importance.”

SUMMARY

Heschel’s mysticism regards existence as a mystery and a wonder. Who invented this? How is it even possible to wonder and to seek understanding? How inadequate are we in comprehension – and yet how amazing to feel the presence of something beyond our expression. Heschel’s question for us is what to do with the sense of awe at the universe: not what is the nature of God, but what is our response to the presence of the Ineffable? The God of the Jews, the God of the Christians and the Muslims, is the God that created a majestic universe, and also inhabits the mystery. It is true that accepting this God takes a leap of faith. And other religions have differing conceptions of the reality behind the mystery. But choosing to find meaning through religion is an alternative to not believing in mystery and meaning. And that makes us alone in the universe.

What do we do with this one wild and precious life that is known to God? The gift of knowing this God is a sense of support and presence, of being cared for and guided. The demands are stringent – to love righteousness and to seek justice – but they are not impossible. We each have a very small part, but we have a great responsibility with our piece of God’s promise – to make that promise live and shine in spite of the burdens and sorrows living has created.

================================================================

[Not used in oral presentation]

This type of God differs from other images. This God does not make demands that are whimsical or fear-based, or related transactionally to sacrifices and rituals. She is not a clockwork God that wrote the laws and made the universe, then stepped aside to let the magic function. He does not live on an Olympus self-sufficient and aloof, unaffected by the deeds and lives of mortals. Heschel’s God also contrasts with the idea that there is a “Fate” that supersedes all actions, human and superhuman. God is not an Aristotelian “unmoved mover, pure form, a kind of pure thought … eternal, wholly actual, immutable, immovable, self-sufficient, and wholly separated from all else” (pure thought). Such “a god needing nothing, will not need a friend, nor have one.”

God is also not a Unity beyond a void, providing order without interaction with humans. The God of the prophets is not a participant in karma – the endless cycles of reward and deeds, deeds and rewards in Buddhism and Hinduism. Karma operates without grace, freedom, repentance or atonement. Nor is God an Omnipotence without responsiveness to appeal, an angry God dealing with intractable sinners. Heschel’s God is a God of pathos, a God actively hoping, caring that men and women, cultures and histories are looking to live in love, justice and compassion.