Downtown Presbyterian Church Forum, 9/29/2019

Good morning again. We have spent two Sundays encountering the writings and philosophy of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. The reactions to him have been positive: I believe he has moved you as he has moved me with his words and his insights. His philosophy appreciates that the world is full of wonders, and that reason can only go so far in appreciating the magnitude of reality.

“The search of reason ends at the shore of the known; on the immense expanse beyond it only the sense of the ineffable can glide. It alone knows the route to that which is remote from experience and understanding. Neither of them is amphibious: reason cannot go beyond the shore, and the ineffable is out of place where we measure, where we weigh.”

If we retain and value the sense of wonder, it can lead to a realization that all we see in the world is not all there is to the world. Maintaining wonder (asking with a smile and a shake of the head – “how is this possible, too?”) does not preclude scientific examination. But it does require a leap of faith that we are better off with radical amazement at the wondrousness of the world, rather than being indifferent to wonder, or complacent or smug with the answers that human reason provides.

If one can accept that understanding is not only rational and logical, then we come to the questions that religions try to address. They are not conceptual questions any longer: the tragedies of the 20th century (Auschwitz and Hiroshima among others) force religions to re-investigate their assumptions and their responses. The situational questions that have always been part of religions need to be re-discovered, and then re-answered. How should we live with one another? What makes a life worth living? What is evil and what do we do with it? How do we find Truth? Heschel believes that religions share a starting point of understanding that mankind is small compared to something much greater, and that human understanding is inadequate to appreciate all of reality.

Heschel’s God is both creator and partner. “The universe is done. The greater masterpiece still undone, still in the process of being created, is history. For accomplishing His grand design, God needs the help of Man. … Life is clay, and righteousness the mold in which God wants history to be shaped.”

Living with this kind of awareness leads to the possibility of sacred humanism. Honoring human nature and human beings, preserving one’s own dignity and the dignity of others is humanism. Adding a religious dimension makes the humanism sacred: our being here and our being together includes the presence, support and expectations of a God. Heschel’s views of a God of the prophets can coexist well with Christian views: depth theology brings religions together, even if creeds separate them.

———————–

Today I want to remind us of Rabbi Heschel’s contribution to political life in his time: that is, how his sacred humanism moved him to connect religion with activism: “I’ve learned from the prophets that I have to be involved in the affairs of man, in the affairs of suffering man.” Justice and compassion are needed not only in private affairs, but in public life and policy.

By 1962 Heschel had established a reputation as a philosopher and theologian, as one of his reviewers said, using language and intuition to coax truth out of the universe. His depth theology was trying to build bridges between religions (recall in 1960 JFK’s Catholicism was a matter of concern). Theologies can divide: dogma is “a poor man’s share of the divine. A creed is all a poor man has. Skin for skin, he will give his life for all that he has.” Depth-theology sought to find common grounds among religions: “Theology is in the books; depth-theology is in the hearts.” All religions are trying to seek, find and share answers to humanity’s embarrassment, indebtedness, and sense of mystery before the Ineffable.

The 1960s would see Heschel’s involvement in confronting (eloquently) difficult social questions: racism in America, inter-religious dialogue (including Catholic doctrine about conversion of Jews), Jews in Russia, Israel’s existence, the war in Vietnam, nuclear disarmament, consumerism in America. How should religions function in a free society? Do they compete or do they cooperate? He stated emphatically and repeatedly, religion needed to speak to absolute values, first of all to the holiness of humankind. “Social ills were due in large part to the trivialization of the human image and the degradation of language …” Heschel was moved to participate in the paradox of living: there could be a possibility of experiencing Heaven on earth, and there could be horror at “discovering Hell in the alleged Heavenly places in our world.” He did not stay in his study.

“The purpose of prophecy is to conquer callousness, to change the inner man as well as to revolutionize history.”

He applies his depth theology: this is an understanding of God starting with radical amazement at the Ineffable, and leading to understanding of the Jewish God as a God of pathos, working through history to call mankind to be a partner in justice and compassion. Heschel asks us to overcome the root of evil, which is callousness, hard-heartedness. And I think we need to challenge ourselves with a difficult question: the social justice and progressive movements can be secular and humanist. Is it sufficient to place faith in human reason and human effort? Or is it necessary to develop a sacred humanism? And if so, then we, those who go to church, have a huge challenge: how do we undo the stigma that religion is irrelevant, dull, oppressive and insipid? These are examples of the situational questions that Heschel insists we ask.

Heschel was exposed to American racism as soon as he arrived in Cincinnati in 1940. He began to speak publicly on this subject in 1958. It was this speech in January 1963 that introduced him to Martin Luther King. He was in fact the keynote speaker at this first interdenominational conference on religion and race.

Heschel is known for his poetic writing, and his philosophical and theological organization often gets obscured by his poetry. It was a frustration to academics that he mixed philosophy and theology, analysis with piety. Here we see his poetry.

Let me use my professor’s themes for Heschel: Remembrance, Reverence, Resistance. Let’s use these themes to make Heschel more accessible.

Heschel uses secular and religious sources to remind us of the traditions and ideals that we value.

Remembrance

- Moses

- Genesis

- Ecclesiastes

- Isaiah and Amos

- William Lloyd Garrison

- Reinhold Niebuhr

- Thomas Jefferson

- Martin Luther King

- Pope John XXIII

These people (all male) were referenced in the essay as models of virtue and eloquence. Their words ring; their messages pierce. The Biblical references and the prophets speak with near-timeless authority. The secular writers stood on pedestals of character and eloquence. Modern deconstructions of their lives and cultures have shrunken and trimmed their pedestals considerably – the pedestals are pretty wobbly. We recall their weaknesses and hypocrisies when we hear of them; we suspect that perhaps all men contain shadow sides that dim their luster. We might suspect that they are “only human” and don’t deserve our emulation. We question the luster of their words: those words could be construed as having power that is contingent to their times and cultures.

At the very least, I would submit, that would be making an either/or choice based on our own self-deceptions (of our own virtue), or our own callousness to virtue in general. Cynicism is self-protective (it was suggested to me long ago that cynicism is the flip-side of romanticism: disappointed when our ideals confront reality, cynics prefer to reject the idea of ideals. They remain angry at the disappointed expectations). Nihilism is self-serving also, by eliminating one’s ultimate responsibility. If we lose our sense of wonder, then even ringing words and piercing messages can be ignored. We then become hard-hearted, indifferent, calloused. Heschel warns that callousness is a source of evil. Indifference to evil is worse than the evil itself.

Reverence:

Heschel gives strong and deep religious foundations of the civil rights movement. (At this time, he cultivated a prophetic look – beard and long hair.) God’s message is audible if we allow ourselves to hear; there are many echoes and reverberations of the message. God is the God of the prophets, searching for mankind to help bring about justice and compassion. With Heschel, the words are a fugue on a theme.

- “Humanity as a whole is God’s beloved child”

- God created different plants and animals. “God created one single man. From one single man all men are descended.”

- “What is an idol? Any god who is mine but not yours, any god concerned with me but not with you, is an idol.”

- “We think of God in the past tense and refuse to realize that God is always present and never, never past …”

- “Equality of man is due to God’s love and commitment to all men.” “Equality as a religious commandment goes beyond the principle of equality before the law.”

- “This is not a white man’s world. This not a colored man’s world. This is God’s world.”

- “The prophets have a bias in favor of the poor.”

- “Reverence for God is shown in reverence for man … the fear we must feel lest we hurt or humiliate a human being must be as unconditional as fear of God. … To be arrogant toward man is to be blasphemous toward God.”

- “I cannot believe that God will be defeated.”

- “Justice is not a mere norm, but a fighting challenge, a restless drive … Righteousness is God’s power in the world, a torrent, an impetuous drive, full of grandeur and majesty.”

- “the universe is done …

Resistance

To complete our responsibility to God and man, we need action, and not only faith and beliefs; not only memory and reason, but will. It remains for us to act. Heschel’s words confront the status quo and present us with challenges and new realities – new ways of seeing reality.

- “Racism is worse than idolatry. Racism is satanism, unmitigated evil. … Racism is man’s gravest threat to man, the maximum of cruelty for a minimum of thinking.”

- “Perhaps this conference should have been called “Religion or Race.” You cannot worship God and at the same time look at man as if he were a horse.”

- “What we need is an NAAAP, a National Association for Advancement of All People. Prayer and prejudice cannot dwell in the same heart. Worship without compassion is worse than self-deception; it is an abomination.”

- “By negligence and silence we have all become accessory before the God of mercy to the injustice committed against the Negroes by men of our nation.”

- Some are guilty, but all are responsible.”

- “… humiliation, the cause of strife”

- “Required is a breakthrough, a leap of action. It is the deed that will purify the heart. It is the deed that will sanctify the mind. The deed is the test, the trial and the risk.”

- “The greatest heresy is despair, despair of men’s power for goodness, men’s power for love.”

- “What we need is restlessness, a constant awareness of the monstrosity of injustice.”

Ultimately, “… religion is not sentimentality. Religion is a demand; God is a challenge, speaking to us in the language of human situations. His voice is in the dimension of history.”

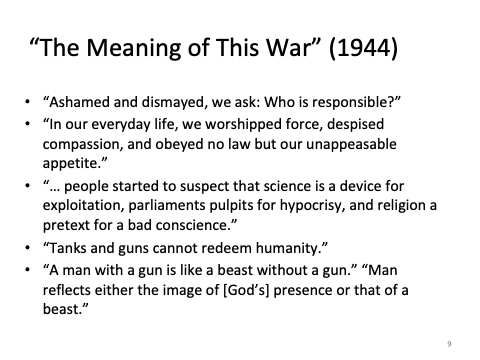

Similarly the other essay, “The Meaning of this War” is a theological and ethical challenge that I think is timeless. It cannot be read as an indictment only of the world that Heschel lived in. This essay was published in 1944. But it was a version of a talk he gave in 1938! This essay is not only a condemnation of Nazism. I am bothered by it, because of the implications it has for our times, 80 years later.

Heschel looks at history as the way God judges mankind’s efforts and errors. World War II with the unparalleled violence, death and suffering experienced by soldiers and civilians was for Heschel a divine judgment for a culture developing over centuries in Europe, not just one type of government. It was not Nazism or militarism, per se, but the spread of poisons that had developed over generations. It was not only National Socialism as a solution to Germany’s post-war shame and poverty – it was unquestioning “rationalism” and “progress” and a culture that valued force and instinct and satisfaction over compassion, truth and justice. It was not just Hitler and Himmler, there were “many thinkers” who scorned the “reverence for life, the awe for truth, the loyalty to justice.”

When prophetic words are spoken (by Heschel and by others) – who will hear? We are living in dire times. Reading this 1944 or 1938 essay, are you troubled by potential parallels with our American exceptionalism? See/Hear the words that are just as prophetic now as in 1944:

- “Ashamed and dismayed, we ask: Who is responsible?”

- “It is so hard to rear a child, to nourish and to educate. Why dost Thou make it so easy to kill?

- “In our everyday life we worshipped force, despised compassion, and obeyed no law but our unappeasable appetite.”

- “… people started to suspect that science is a device for exploitation; parliaments pulpits for hypocrisy, and religion a pretext for a bad conscience.”

- “Tanks and guns cannot redeem humanity.”

- “A man with a gun is like a beast without a gun.” “Man reflects either the image of [God’s] presence or that of a beast.”

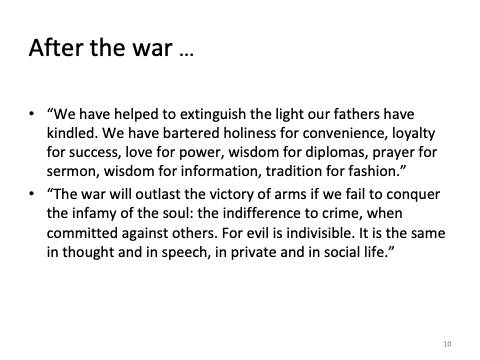

Even before the war had ended, Heschel wondered if the culture had changed, whether humanity had learned its lessons at all.

“We have helped to extinguish the light our father have kindled. …”

“The war will outlast the victory of arms if we fail to conquer the infamy of the soul: the indifference to crime, when committed against others. For evil is indivisible. It is the same in thought and in speech, in private and in social life.”

One of Heschel’s themes is that self-delusion is a powerful and insidious force. We too often lie to ourselves in order not to lose our sense of goodness, worthiness, status or competence.

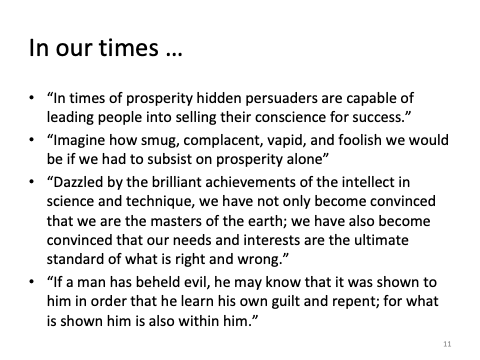

Elsewhere (not this essay) Heschel makes a parallel between the appeal of Nazism in times of poverty, with the appeals of consumerism in times of prosperity: “In times of prosperity hidden persuaders are capable of leading people into selling their conscience for success.” Elsewhere he ridicules “how smug, vapid, …. In 1967 he laments that so soon after Auschwitz and Hiroshima, America was forgetting that “greed, envy and reckless will to power” would lead to tragedy for individuals and societies. History once again would judge – this time America.

It is not the doctrine or the politics or even the political system that is corrupting. Heschel warns that it is the attitude: is humanity the pinnacle of meaning, or is God?

Some are guilty, but all are responsible. “If a man has beheld evil, he may know that it was shown to him in order that he learn his own guilt and repent; for what is shown to him is also within him.”

So we come to the conclusion of my comments on Rabbi Heschel. I hope I have provided a sense of the majesty of his words and conduct. Paraphrasing him, I would ask ourselves, “Not how much Heschel have we gone through – but how much of Heschel has gone through us.” One of his students quoted this: “whoever quotes his master’s words, it is as if his lips still move from the grave.” It is marvelous for me to imagine Heschel’s lips are still moving.

Summarizing my presentations:

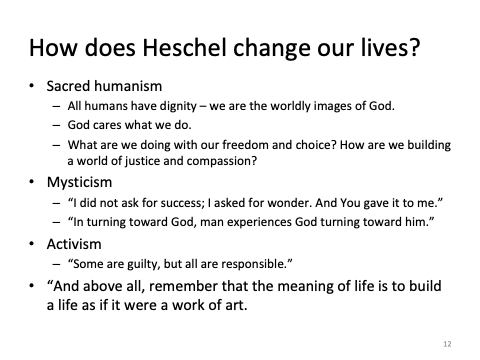

In the first week we discussed 3 tenets of Heschel’s sacred humanism: that all humans have dignity, by virtue of our being worldly images of God; that God is a God of pathos – Someone who cares about what individuals and groups do; and finally that God needs a partner to bring His vision of heaven to earth – that justice and compassion, righteousness and mercy are the virtues that mankind should live by. God is always in search of humans.

In the second week, we touched on Heschel’s analysis of how we might come to appreciate the presence of God in our lives. He maintains that we must maintain a sense of wonder. With it, connections and awareness grow. Without it, we are stuck with our human perceptions. He said after his massive heart attack in 1969 words that had written in the 1930s: “I did not ask for success: I asked for wonder. And You gave it to me.” When we turn toward God, we realize that God has been present all along, waiting for us to seek him. Prayer and Sabbath and theology provide time and training and opportunities to develop the sense of being of concern to God. “Know thy God” becomes the highest priority, rather than “Know thyself.”

And today we heard some of Heschel’s prophetic concerns about societies that have forgotten to look to God. Racism in America and inhumanity in Nazi Germany have similar roots – neglecting concern for other humans, due to concern for one’s own interests. When we read Heschel, he points out our shortcomings but also offers us reasons and means to mend our ways.

“And above all, remember that the meaning of life is to build a life as if it were a work of art.”