Downtown Presbyterian Church Forum, 9/15/2019

It is with great humility that I begin this series of forums. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel is a hero of mine, and I wish to share some of his amazingness with you. Heroes are people who confront and overcome trials; they inspire us and remind us of what is possible in the human spirit; they point a way for doing the difficult. Heschel serves as a hero to me in all these regards.

If you are a seeker of meaning, Heschel’s writings are an “embarrassment of riches”. He addresses questions of meaning: How is it that we are here together? Why are we here? What are we meant to do with our time together? His legacy also is a reminder of how fragile culture can be – how culture and wisdom can be lost, how we need to be mindful of the roles we play in passing on truth, knowledge and experience.

I am far from a Heschel scholar – more like a Heschel aficionado. During a sabbatical at Union Theological Seminary in 2013, I took a course on Heschel; Prof. Cornel West organized readings around Heschel’s piety, prophecy and poetry. Preparing these talks I have re-acquainted myself with those texts, as well as several others. (I have brought a reference list of relatively short pieces, both by him and about him.)

The message I gathered, which I believe is a paraphrase of what Heschel said, could be summed up as follows: We can re-invigorate our personal lives and our civic lives when our actions evoke God in this world. God lives beyond us and within us; we cannot articulate what he “is” (human expression is inadequate), but we can sense that God exists and cares – God cares about us, and cares what we do – God needs a partner. The more we can live in awareness of that, the more we can live up to our human potentials.

Today let me try to review Rabbi Heschel’s life and summarize some of his philosophy (!). Next week I will try to describe the mystic quality of Heschel’s Judaism – how does one appropriate religion anew for oneself, so that it does not become stale and irrelevant? In the third forum, I will describe how Heschel’s prophetic awareness (awareness of humans mediating between God and mankind) might move us to recognize and resist the callousness and evil within and around our lives.

Heschel’s commitment to actions based on compassion and justice, with God as the source of meaning and purpose, define an attitude that we can call Sacred Humanism.

================================================================

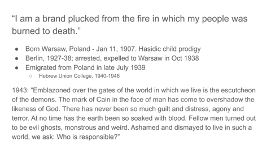

All efforts to understand Heschel should begin with his remarkable biography. He was grounded in Eastern European Jewish (Ashkenazic, not Sephardic) culture, and had his former life torn away in WW2 – he understood tragedy, and was well aware of the lives and martyrs of Jewish history. His first languages were Yiddish, Polish, and Hebrew, and his published scholarship was in German and Hebrew before he published anything in English. In his first American book, in 1950, “The Earth is the Lord’s”, Heschel remembers and honors his culture of origin as a culture living with spiritual integrity: not only individuals but an environment dedicated to living “in accordance with the dictates of an eternal doctrine.” It is an elegy, and it is perhaps difficult to imagine a society as ideal as he portrays. It is also a lost culture, of course, intentionally destroyed. His words are monuments to that lost world.

He was raised as the son and grandson of rabbis, going back 7 generations. Even within that lineage he was regarded as a prodigy, called on when still a child to comment on Hebrew scripture. He wanted secular education in addition to religious education, so he chose to attend college in Berlin in 1927, at that time the center of European intellectual and cultural life. He studied philosophy and theology, and learned how much German/European patterns of thought differed from his earlier traditions. His doctoral dissertation The Prophetic Consciousness (Das Prophetische Bewusstsein) was a work exploring the contrasts between Jewish and European modes of thought. Although he completed his oral exams at the University of Berlin in February 1933, Hitler’s rise to power made it impossible for him to get his dissertation published for almost 3 years (publication was needed to be granted a diploma). He wrote, published and lectured throughout Germany as Hitler and the Nazis took power; he took over Martin Buber’s position in Frankfurt when Buber went to Palestine in 1938. The Gestapo arrested him in the middle of a night late in October 1938, and expelled him because he was a Jew with a Polish passport. He had to find a way to leave Poland, and was finally offered a position at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati as one of 6 Jewish Scholars in Exile who were granted US visas. He left Poland in late July 1939 just 6 weeks before the Blitzkrieg. Nearly everyone he had known as a child perished in WWII. He never returned to Eastern Europe. “If I should go to Poland or Germany, every stone, every tree would remind me of contempt, hatred, murder, of children killed, of mothers burned alive, of human beings asphyxiated.”

Hebrew Union College was a Reform institution, and Heschel was unhappy there. His European and Orthodox habits made him the butt of jokes by his young American students. His Jewish colleagues did not share his horror at the Holocaust. In October 1943 while still an immigrant on a visa, he marched in Washington DC with Conservative and Orthodox rabbis, to ask for support to rescue European Jews facing the “Final Solution”. The US government as well as most of the American Jewish community did nothing. He was reliving the silence of German Christians in the 1930s. He had to wonder how that could be. But he was finding his rhythm and his voice. In 1943 he published an essay in English which he had previously given in German in 1938. His mastery of English was evident: “Emblazoned over the gates of the world in which we live is the escutcheon of the demons. The mark of Cain in the face of man has come to overshadow the likeness of God. There has never been so much guilt and distress, agony and terror. At no time has the earth been so soaked with blood. Fellow men turned out to be evil ghosts, monstrous and weird. Ashamed and dismayed to live in such a world, we ask: Who is responsible?”

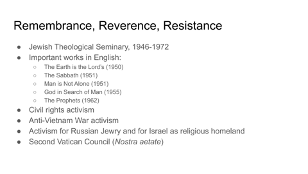

Professor Heschel went in 1946 to Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, a Conservative Jewish institution. He remained there for 26 years, until his death in 1972. There he was professor of Jewish Ethics and Mysticism. Also in 1946 he became a US citizen and married; their only child, daughter Susannah was born in 1952. Susannah grew up to be a professor of Jewish studies at Dartmouth, and has edited several anthologies on her father’s works.

Between 1950 and 1962 he published his most important works in English. (He also had substantial bibliographies in German, Yiddish and Hebrew!) His academic works were based on incredibly referenced knowledge of European and Hebrew classics. But the books in English had comparatively few citations as they were meant to speak to lay readers. His reputation rose after Reinhold Niebuhr gave a glowing review of Man is Not Alone. His works articulated for a post-war society why religion was still relevant, and particularly the Jewish religion. When he re-published his doctoral dissertation in 1962 as The Prophets, he gave biblical voice to resistance against social injustices.

In 1963 he met Martin Luther King at the first National Conference of Religion and Race, and they recognized similar spirits in each other. He sent a famous telegram to JFK that winter that concluded: “A Marshall Plan for aid to Negroes is becoming a necessity. The hour calls for moral grandeur and spiritual audacity.” He marched with King from Selma to Montgomery in 1965. Heschel said of King, “Where in America today do we hear a voice like the voice of the prophets of Israel? Martin Luther King is a sign that God has not forsaken the United States.” King would have celebrated the 1968 Passover Seder with the Heschel’s had he not been assassinated a week before that.

He joined King also in resisting the war in Vietnam, and endured similar questioning and resistance about whether it was correct to do so. He became colleagues with Daniel Berrigan, William Sloane Coffin and other anti-war leaders. (Coffin often called him Father Abraham). At one seminar, Professor Heschel asked his students to debate whether gelatin was kosher, and after several minutes of spirited debate he followed up with the question, Is napalm kosher?

Rabbi Heschel was also active in efforts to support Russian Jews – another Jewish people and culture threatened with extinction. He was a supporter of the state of Israel, as a religious homeland, including the restoration of Jerusalem, but he also was troubled by the political dilemmas raised after the 1967 War.

Someone has said, “Rabbi Heschel’s work, unlike other philosophers’, is directed not only at the mind, but at the heart and the will.” Let me offer a few tastings of Rabbi Heschel through quotes from his writings.

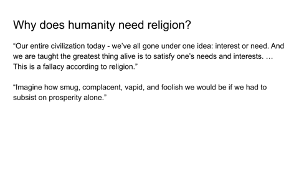

In the 1940s and 50s, the social sciences seemed to be better guides and explanations of behaviors than religions. “Our entire civilization today – we’ve all gone under one idea: interest or need. And we are taught the greatest thing alive is to satisfy one’s needs and interests. … This is a fallacy according to religion.” Heschel struggled with the idea that religion and morality were human impulses, developing from some combination of biology, psychology, sociology, esthetics, etc. – that ideas of God were the result of environment. He rejected that conception. “Human existence cannot derive its ultimate meaning from society, because society itself is in need of meaning.” The negative example was Nazi Germany – there right was defined as what served the needs of the German people. It was rational, but it was wrong.

He lived in America where a hopeful secular humanist outlook was trying to make sense of life after Auschwitz and Hiroshima. There was hope and promise in economic opportunity. There seemed to be a need to forget what harms human beings could be capable of. What he said in the 1950s seems even truer now: “Imagine how smug, complacent, vapid, and foolish we would be if we had to subsist on prosperity alone.”

Rather than defend religious behaviors or beliefs, Heschel’s works examined what experiences seemed to trigger religious sensitivity – what are the questions to which religion is an answer?

In next week’s presentation, I will work with Heschel’s examination of why and how we come to need a sense of meaning – how wonder, and awe and reverence lead to awareness of Something Else. (We need to retain a sense of wonder.) I will try to do justice to his awareness of a God of the prophets, a God who cares. He argues that God is not an idea (either philosophical or natural), but a Subject: behind and beyond what we see and feel, there is Someone who wants mankind to pursue justice and righteousness. This understanding of God might begin in mysticism (our awareness of belonging and connection to Something Greater), but lives in history: The Bible to Heschel is a record of God in search of man – from Adam on, the question has been: “Where are you?” That kind of understanding enriches and clarifies our roles. LIke Adam, we can run but not hide from our being of concern to God.

He rejects that our rational capacities are sufficient. “Just as you cannot study philosophy through praying, you cannot study prayer through philosophizing.” “We are in need of spirit in order to know what to do with science.” He rejects that complacency and inner peace are the goal. He recognizes that evil exists in the world, and that truth is difficult to find. “One of the major inclinations in every human being is a desire to be deceived. Self-deception is a major disease. … We live in a world full of lies.”

He is very Jewish in his faith and practice, but the God of the prophets, the God of pathos is perhaps only a small step from the intervention in history that resulted in the Christian church: Christ was a prophet in his time who, by human standards, failed at his mission; he was killed by the state, only to be … resurrected (!). It was an intervention in history as momentous as Mt. Sinai. The message carried by the Apostles and Paul and beyond promised that the God of the Jews could also be God to the Gentiles. This holy catholic (universal) church has spread globally, and yet world peace is not at hand. As Heschel has said,”In this eon diversity of religions is the will of God.” The deeds of humans still matter. The God of the prophets keeps trying still to reach us – how are we to respond?

So let me elaborate on Heschel’s sacred (Jewish) humanistic view of the world. It undergirds so much of Western history and culture.

First, Man is created in the image of God. This concept is radical and foundational. Individuals and humanity are created in the image of God. Before Judaism this was not a concept. The implications are profound. It means that gods and humanity are not separate and unequal. It means that we are endowed not only with “unalienable rights” but also unalienable dignity, worth, capacities and freedoms. “The human is a disclosure of the divine, and all men are one in God’s care for man. Many things on earth are precious, some are holy, humanity is holy of holies.”

Because God is invisible, and you can’t live without God – God created a reminder, an image. “What is the meaning of man? To be a reminder of God. God is invisible. And since He couldn’t be everywhere, He created man. You look at man and you are reminded of God … As God is compassionate, let man be compassionate. As God strives for meaning and justice, let man strive for meaning and justice.” Can we see God in seeing our neighbor?

Not only is God present, but the God of the prophets is a God of Pathos – Someone full of feeling and concern. The prophets, speaking for God, castigated the rich and powerful because they did not take care of the widows and orphans. I don’t find this kind of God to be in conflict with the Christian God – a God who made a new covenant in the life and resurrection of Jesus. The point is, God will always care.

Third, as a part of that caring, God has expectations of humans and of mankind – there are covenants. The individual and the social are not separate for this God. The God of pathos cares about the morality of humans and humankind – our purposes and manner of living. The biological functions (the animal tendencies) are not evil in themselves – it is not a Greek duality of flesh and spirit. Rather, how one lives one’s biology is crucial: how does one serve God in actions, thought and word; how much love, justice and righteousness is in our hearts and actions?

There is a challenge, too: given freedom and knowledge, humans tend to make a mess of it. Even the birth of Jesus as an intervention of God in history and nature has not rescued us from the too-human tendencies to ruin Creation. Our animal natures are limited, and our desires for comfort and delusion seem limitless. “God is waiting for us to redeem the world. We should not spend our life hunting for trivial satisfactions while God is waiting.”

Together these strands can create meaning for life: we are images of God, God wishes well for mankind, God needs the partnership of mankind to realize His vision and values. These strands provide human and sacred answers to the questions of why we are here, and how are we meant to be with each other.

Life can be random but it is not absurd any longer – there is meaning beyond absurdity. There is choice, and there is responsibility. Heschel believes there is God-centeredness – concern for the concerns of God, OR there is self-centeredness, concerns for the interests of self and tribe. The latter, a secular humanism, might inspire and sustain persons and societies in good times. But will it sustain faith in the not-so-good times: the troubles, the tragedies, the Holocausts? How is one to reconcile the evil and suffering in the world with its grandeur and beauty? Next week I will try to do justice to the mysticism of Heschel, which can love and seek God, even when it seems God is absent from the world: it is a foundation of faith in God, not in human nature.

================================================================

Summarizing today, Abraham Joshua Heschel came to America from a culture that the Nazis tried to destroy. But Rabbi Heschel said that the chosenness of the Jewish people, Jewish culture, Jewish history is more than a legacy for Jews: it is to be an example to the whole of humanity – how to live in relationship to one another, how to remember the past in order to live in the present, how to revere persons and traditions, how to live with triumph and tragedy. We do not have to be Jewish to hear these truths.

Heschel’s “message to young people” at the conclusion of his 1972 Carl Stern interview is universal – and founded on sacred humanism (without saying so): “I would say, let them remember that there is meaning beyond absurdity. Let them be sure that every little deed counts, that every word has power, and that we can, everyone, do our share to redeem the world in spite of all absurdities and all the frustrations and all disappointments. And above all, remember that the meaning of life is to build a life as if it were a work of art. You’re not a machine. And you are young. Start working on this great work of art called your own existence.”