Ethics Grand Rounds at RGH, 10/27/2015

Good afternoon. Thank you for coming to this talk. I am excited (and nervous) to share my thoughts and concerns. They are not fully packaged thoughts – I offer the beginnings of things we need to talk about more. What I hope to do is to remind you/us why we care about patients, and why it is sometimes so difficult to care. I hope that what we learn today can help us continue to care, and not just deliver goods and services.

I want to thank you for showing up today – both at work, and at this talk. For taking time from a busy day to listen to someone most of you don’t know. Thank you, and thank you again.

Taking care of patients is difficult work. It is an occupation with a long and honorable history. In recent years it has also become an industry that has had to deal with delivery of $3.2 trillion of services. Our hospital is a small part of that industry; our daily roles are a small of that hospital. What can we do in our small but important part? But also what can the hospital do for us?

================================================================

My experiences are in internal medicine, critical care and pulmonary, as well as some in palliative care. I was burning out a few years ago, finding it difficult to find meaning in the daily grind of taking care of my patients. I was hurt and angry about having to spend so many hours trying to understand patients enough to be able to get them through their illnesses, trying to provide support and healing if possible, but also support when healing was not possible.

I was struck by the presence of suffering, and how little we noted it, discussed it, dealt with it. I applied to the Union Theological Seminary for a sabbatical. Here are words from my application: “I am a physician who sees suffering daily in many forms. Suffering is universal, but some manage their suffering better than others. I wish to learn more of the issue of individual suffering and how it relates to the medical care of chronic illness and dying. The theological dilemma I have seen is that religious belief systems are neither necessary nor sufficient to deal with suffering – so instead, what elements allow consolation in the face of mortality, and how can they be applied to ease suffering?”

In the spring of 2013, I spent a semester at Union, and since then I have tried to limit my clinical time. I needed time to explore and think about how suffering and health work relate to each other: how they work together and how they don’t. This talk is a sharing of that effort.

My thesis is that: in all of our daily roles (clinical, administrative and others), we encounter and try to relieve suffering, and therefore we need to maintain and support the capacity for compassion – in ourselves and in our environment. Change begins within individuals, and I offer my ideas to help us recognize that we can change, to be better for ourselves and for our patients. But lasting change also requires institutional support – so I have invited members of our hospital administration to listen, too. Thank you all for coming.

The health care industry is not like any other industry, and so its goals and visions need to be different. Health care is different because it deals with persons in decline and suffering; every other industry deals with hope and growth. Our surrounding material and profit-driven culture would have us think that more is better, and enough is never enough. Taking care of patients requires some of that, of course: hope in the face of illness is still necessary. But patients arrive at our doors because they are suffering: besides physical pain, they have dimensions of suffering related to uncertainty, loss of connection, loss of meaning, and fear of all of these. We are the locale in society that collects and concentrates experiences of loss and decline. You/We are the people who encounter it daily, are affected by it, and need to find strengths to do it again tomorrow. So thank you for doing so: it is our worthy calling.

We have to be careful that industrial methods do not ignore the unique nature of health care. What we provide is more than safety and value, a device or a drug, or even excellent management. Since suffering is pervasive, we also have to address how to recognize it and relieve it. It is my position that we cannot do a good enough job if we see ourselves as only delivering a “product.” We also need compassion. Health care is also in the relationship, and because suffering is in the needs of patients, compassion has to be in the response.

So we need to understand suffering somewhat. But more importantly, we want to understand how to be compassionate in its presence, how not to be callous. I want today to talk about compassion, and barriers to compassion. I will structure my comments around awareness of delusion, desire and anger as barriers. And I hope that we can acknowledge barriers at a personal level (change must begin within ourselves), as well as in our environment (lasting change will require awareness and support from our leadership).

Many of you have seen this video from the Cleveland Clinic. I think it’s useful to see again, because it is good. So let’s watch it together.

Empathy and compassion are related, but they are not the same experience or skill. Empathy is a sensory function – the ability to receive emotional information. It can be taught, and it can be developed. It requires presence and it requires emotional awareness. Being empathic can hurt though, and we learn, consciously and unconsciously, how to protect ourselves from the painfulness of patient suffering.

Compassion is the wish to relieve suffering. It takes awareness of suffering first – that is where empathy is needed. Compassion is not the help itself: there are many skills still needed to express compassion. Compassion is an attitude, an essence, a wish to act in a certain way. It is one of my themes today that that attitude has atrophied in the modern health care environment. The atrophy follows from the barriers we will discuss: ignorance and delusion, desire and wanting, and anger remaining from previous losses and hurts (our own suffering)

Our selves and our minds are what we give to our patients, not only our skills and technologies. Hopefully, when we face our own declines, there will be someone there with compassion to support us too, however empty-handed they may otherwise feel.

Suffering is a universal human experience. Dr. Eric Cassel wrote in his seminal book The Nature of Suffering and Goals of Medicine that suffering is personal – so attention to suffering must attend to the Person.

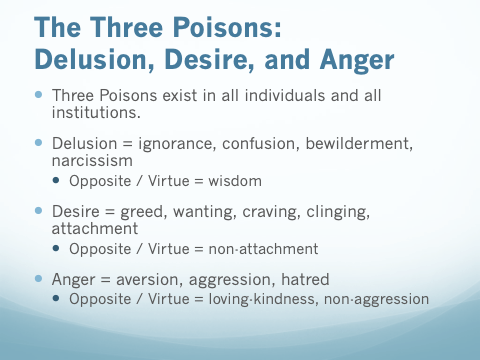

One of my classes at Union was on Zen Buddhism. Buddhism has addressed the issue of suffering directly – it is the first of the Four Noble Truths, that suffering is part of all human experience. In my courses on Buddhism and in a conference on Christian-Buddhist dialogue, we were reminded that the Three Poisons interfere with compassion. I will not attempt to convince you that practicing Buddhism will release you from suffering, but I will borrow from this religion and philosophy. The Three Poisons are delusion, desire and anger.

I will use this Buddhist structure out of convenience – like rubrics in any religion, they are useful to organize discussion and organize reality. For instance, I could instead use the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, to focus on greed, status and pride: the three temporal desires that prevent men from approaching an ideal of Christian spiritual living. The point is that religion and spirituality seek to provide meaning and comfort to lives.

Dr. Cassel suggests that suffering occurs when there is loss in important dimensions in one’s life. Coping occurs when strengths in other dimensions can be called on to compensate. One of those dimensions is the transcendent: that we are connected to something larger than ourselves. My observation is that the “transcendent dimension” is the one we discuss least in medicine. That is one of the things I am interested in now: what remains when illness and aging deplete us? Suffering and loss are the final common pathways, but connection to something bigger is a strength that supports the ability to cope with life, deal with suffering.

The three poisons are Delusion, Desire and Anger

The original Sanskrit terms carry nuances that we cannot fully appreciate in a cross-cultural context. I choose Delusion, Desire and Anger. There are other words that have been used. ***

Let us explore each of these in more detail, emphasizing their individual and their systemic manifestations. Remember, I am trying to understand how we can retain compassion and resist callousness in what we do – which is to encounter suffering– every patient, every day.

Delusion and ignorance is the most important of the Three Poisons.

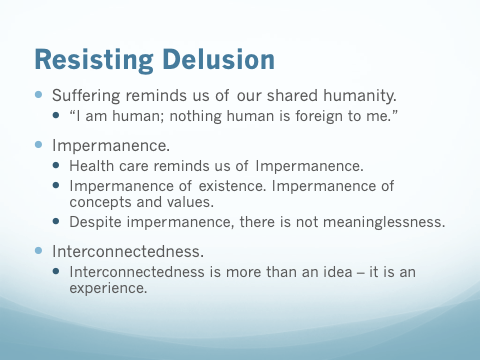

Health care, if we wish to consider it, provides the greatest opportunity to recognize and appreciate the impermanence of existence. Illness and aging are guaranteed to everyone. As we face losses, as we lose competency, relationships, wealth, health, a sense of meaning, Mind: what remains? It is delusional to believe that suffering only happens to others. It is delusional to believe that one is set apart.

“Impermanence” also means that what seems critical and important to one person or one culture can seem completely different from another perspective. What value is there in concepts, if the value of a concept can change? We need therefore to be careful in our assessments of values.

Despite impermanence, however, there is not meaninglessness; there can be, there is interconnectedness. This is where experience matters– not historical experience (memory), but the experience of presence, of timelessness. It is what Zen meditators seek when they eliminate awareness of ideas, feelings, sensations, and even impulses. It is what religions counsel when they encourage prayer and to be in the presence of God. It is what groups experience in tragedy (9/11) and in triumph (sporting victories). It is what we feel at the birth of a child, the death of a loved one. This sense of interconnectedness is not an idea; it is an experience.

It is suffering that provides the most pointed reminders that we share our humanity. “I am human; nothing human is foreign to me.” This statement can be a description of experience, but it can also be a credo, an organizing principle.

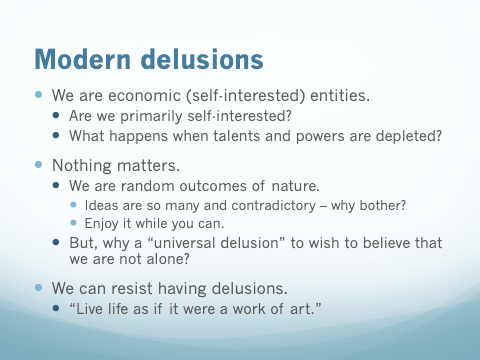

I offer the ideas of Impermanence and Interconnectedness to counteract two modern assumptions. First, there is the organizing principle that we are economic or narcissistic beings: that self-interest and individualism are of prime importance. We will touch on this again when we discuss Greed, but for now I will claim that rampant individualism does not meet our needs when our talents and our powers are depleted. Illness awaits the narcissist as surely as it awaits the rest of us. What then? We are individuals clearly, but we perhaps we are also meant to live in community, in support, in interconnectedness.

Second, there is the organizing principle that nothing matters – that our biology and our histories have been created out of randomness, accidents – the world is absurd, devoid of meaning. The profusion of ideas and the conflicts that arise from competing ideologies can certainly make it seem that any belief system is suspect. Why bother then? Why not live as if there were no tomorrow – YOLO? For this view, the prospect of suffering reminds us that doing as we please has its limits. Thus, it can seem to be a reason to enjoy it while we can.

But let me also offer an alternative or addition: when we create lives that value compassion and support to others, we provide models for others to do the same. We can, if we choose to, connect to something greater than ourselves. Not to give up our individuality, but to use it, to create a contribution.

Freud said it is a “universal delusion” to try to feel that we are not alone. But if it’s so universal, perhaps it is essential. Are we alone? Or are we meant to be in community? Should we grow up, or should we wake up?

I believe another great delusion is that we can’t make a difference. Another influence from my sabbatical was Abraham Joshua Heschel, a rabbi, mystic, philosopher and activist, who took the pain of his losses in the Holocaust and transformed the pain into an understanding of how God cares about the world of Man. Heschel said there is always a need for openness to wonder, and to the idea that there is a meaning beyond absurdity. For many it is the idea that we are not alone – that God exists and cares enough to provide guides (Torah, Jesus, Quran). For others it is the wisdom of sages on how to live in communities (Buddha and Confucius, to name only the most prominent).

We can change our delusions; we can resist delusion. We can choose not to live as meaningless fragments, but to live connected. We can live our personal and work lives compassionately, creatively, supportively. Heschel also said, “remember that the meaning of life is to live life as if it were a work of art.”

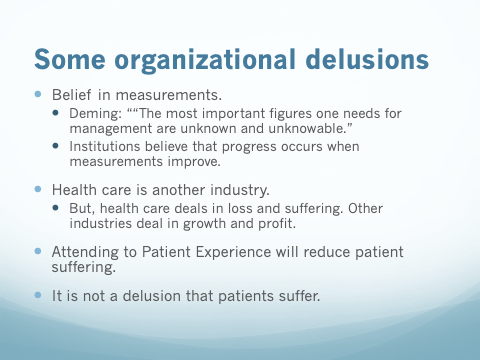

Acknowledging the insidious presence of delusion can help us as an organization also. We can and must search for delusions. One institutional delusion relates to the belief that progress occurs when measurements improve. But even Deming (the guru of measurement as a tool of management) stated, “The most important figures one needs for management are unknown and unknowable.” Ideas are certainly impermanent, as we see in the replacement of management ideas year after year. Outcome measure are more complex and more numerous because simple measures simply measure quality. There needs to be creative leadership to guide improvement in the processes that address suffering. It is the gorilla in the room. Health care deals with loss and suffering, so we might want to be wary of methods and assumptions from growth and profit industries that might not transfer adequately.

There is the beginning of attention to this issue, as Patient Experience becomes a concept to motivate a new series of measurements. (After a few years of stumbling with Patient Satisfaction as a goal, it became obvious that patients did not stop suffering when they received good service.) Awareness of the Patient Experience is at least organized around a plea for empathy and awareness about suffering. In introducing a bundle of new measurements, it is claimed that suffering can be analyzed into components that can be addressed.

But an ongoing delusion may persist, even when the words suggest that there is attention to suffering. A delusion will persist, I fear, because there will mostly be attention to the measurement of suffering. Data does not provide meaning, and attention to data often distracts from the care of patients. The compassionate care of patients is the purpose of health care, and leaders must be careful that the processes of care and their measurement promote and do not hinder that focus.

It is also a delusion to believe that Health Care is a business where success can be measured in dollars or awards. We deal in human capital and human outcomes. We have to be careful that industrial theories and industrial methods do not alter the focus on patients. In this context, the re-definition of health care as the care of populations is a sneaky and even evil intrusion of industrial and economic terminology. Populations are statistics, and we would do well not to deal with people as statistics. We should acknowledge the introduction of this concept, we can work with it, but should also call it out and resist its de-humanizing and callousing influences.

I do not have a solution to this issue. Ignorance and delusion after all are part of being human. We cannot escape the need to feel some sort of mastery of some our behaviors. But we need not satisfy ourselves with believing that our job is complete when we have improved our measurements. We could ask ourselves where there are remaining delusions.

It is not a delusion that patients suffer. There will be suffering, and we cannot escape or deny or spin that fact. The Dalai Lama said, “Compassion is the wish for another being to be free from suffering.” We must act out of compassion, individually and as an institution: we cannot fix suffering, but we can support one another in our struggles, and we can hope to relieve some of it. Rabbi Tarphon said, “The day is short and the work is endless; it is not necessary for you to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.”

Let us now introduce an appreciation of Desire as another barrier preventing expression of compassion. For Buddhists, the second of the Four Noble Truths is that all suffering is the result of desire. There are many synonyms to use, because Desire has many expressions. Words such as Greed, Craving, Wanting, Clinging, Attaching have also been used also.

Craving, wanting and desire do not exist only in regard to money and riches. Desire for status also damages relationships and can interfere with compassion. Desire for stability and security can as well. A return to an imagined past is a craving. Desire includes the wish not only to acquire more, but also the wish not to lose something valuable. It is no wonder that Desire is one of the Three Poisons, a cause of suffering.

The connection between desire and suffering is a valuable contribution from Buddhist thought. One Zen master once suggested, “Suffering in America is a sin against the hopes of the rest of the world.” It helps to ask oneself when one is suffering if part of the problem might be undue craving. When does wanting too much create suffering?

It does not stretch the imagination by much to recognize the parallels in health care. When it comes to illness and mortality, the urge not to lose becomes more demanding and understandable. Of course, “you have nothing if you don’t have your health”. Of course the time together seems more important, the closer that death seems. Treatments that offer the possibility of a few more weeks or months are always tempting.

But the health care industry also creates appetites and expectations. Novel therapies benefit patients of course, but often new devices and drugs do only a slightly better job than older ones, with companies and stockholders benefitting more than patients. Offering drugs and procedures to prevent and restore a semblance of health is easier than counseling about limitation and desiring less. So health care has become an industry mostly about delaying illness and death, not about alleviating suffering or supporting compassion.

Richness in life can come not only from having much, but in not needing as much. We could try to want less – recognize and resist Desire and Craving. When I consider that I don’t need or want a a Lexus, I could feel I don’t need to work as desperately. I might then create time and energy to attend to developing my capacity to relate better to those around me. As they say, no one on their death bed wishes they had worked harder.

This does not preclude behaviors to earn a living – we are not advocating deprivation exactly. But I hope that health care at our level – the level of physical contact with patients – does not become an economic encounter, a commodity exchanged between a “provider” and a “client.” Rather, there can be and maybe should be recognition that taking care of the unfortunate (the widows and orphans) is an act of piety in Judaism; that supporting the sick is an example of taking care of the body of Christ in Christianity; and despite accidents of time and circumstance that have placed us in these particular relationships, we still share interconnectedness (Buddhism). In that recognition, there could be less emphasis on money as the prime measurement of value in our relationships.

Desire also exists at an institutional level. Fiscal responsibility is important. It is a difficult job, and we need to be thankful that there are those watching the bottom line: without resources, the task of providing for patients would be impossible. “No mission without margin.”

I have often quoted Dr. Rick Sterns: “In France death is a tragedy, and in England it’s a duty. But in America, death is an option.” It is both Delusion and Craving that imagines that death can be an option. And institutions have contributed to the Wanting.

There is great self-interest in avoiding honest discussion of the limits of health care. Institutionally and individually, Greed appears in the offering of procedures that appeal to the desires of patients: a joint replacement that might or might not relieve pain; the catheterization that might or might not relieve uncertainty. Similarly, desire and greed participate in decision-making when providing a new service or revenue stream that defers to someone else the inevitable need to discuss mortality and cost. The goal of increasing individual and institutional revenue always becomes a factor that tips the balance in favor of doing more. Even if we do that, let us also share resources to enhance the possibility of eventually wanting less.

Craving also drives the institutional mission to maximize billing. It trickles down from administration to providers: salaries are connected to productivity, as if “productivity” is the prime value. But doing so without acknowledging that loss of contact time reduces the opportunity for support of patients and families with illness. Hospitals chased incentives to use electronic records, and electronic records were sold as a means to make medical care more practical; but so far Epic (the company) has benefited more than hospital systems, and hospitals have benefited their bottom lines more than their patients.

Medicine and surgery have allowed the possibility of delaying illness and death. But illness, decline and death are not options. Sharing those heartaches (not pretending them away) through compassion might lessen the burdens for others. Allowing for Less and not craving for More might reduce demands for health care resources that are truly finite. Changing the demands in health care requires institutional change of course. Desire and Craving can be recognized and resisted – but it starts within ourselves.

Sometimes (I hope often) revenue and compassion are compatible: a Both/And approach is possible. But sometimes unfortunately, there really is a trade-off, that it has to be Either/Or. It is not only someone else who faces these conflicts. We all do and perhaps will, and recognizing that Desire and Craving do contribute to suffering can help us decide when we are faced with our dilemma. How do we prepare ourselves to act as if Death is not only an option?

Lastly, we turn to Anger. Once again, my purpose is to describe forces that prevent us from attending to suffering. Unexamined anger can lead to callousness, so we have to “go inside” to examine it. Change, to be more able to be compassionate, still begins within oneself.

Delusion and Desire involve ideas and appetites; Anger deals with our emotions. Emotions interact with ideas and appetites. So anger also interacts with our beliefs and our desires. It’s a tough topic to discuss, and we should probably set aside time some other time to explore it. Today, I will only touch on some of its complexities.

I believe Anger can be poisonous, but not all anger. We are not living as monks, cloistered in contemplation, so we have to deal with anger and emotions. My two themes for this section are: 1) that Anger relates to hurts and frustrations – our own sources of suffering; and 2) that anger is a signal that something is wrong, and something might need changing.

In the Pixar movie Inside Out, Anger is triggered by a sense of unfairness. If we examine “unfairness” though, we can see that unmet expectations play a role. Related to that, we also discover that a sense of hurt and violation accompany the experience. Unmet expectations, hurt, violation – let’s remember these components whenever we feel or discuss anger. We are also suffering when anger is raised.

Acting out of anger (which is very different from recognizing and feeling anger) is a poisonous thing. We have to be careful not to allow anger to justify actions. It is a gift of Buddhist thought to recognize that actions based on anger do not build compassion and connection, but only fuel further injury, suffering, and disunity.

Not all anger is bad: the presence of anger can be like the fever, the nagging pain, the abnormal lab test that pokes its way to attention, indicating that something is wrong. Many of us have heard the Serenity Prayer: “God grant us the serenity to accept the things we cannot change, the courage to change the things we can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” It is often Anger that signals that something needs changing. The changes sometimes need to be internal. But sometimes anger signals that there is injustice in the world: there can be righteous anger, a call for systemic attention not compliance. We need to respect Anger as a valuable signal.

Your presence here today as members of the helping professions is a result of your talents and temperaments, parental expectations, social rewards, and your creative integration of all of that. We have our rewards – externally there is status and security; internally we can feel of mastery and competence. But along the way in all of us there have been hurts that were not grieved, hopes that were lost, expectations that were betrayed. The sacrifices and the deferred gratifications that we have made (the “have to do” things) have wounded us. My belief is that to the extent that we can reflect and accept that hurts are part of whom we have become (it is painful, but it has formed what is now Me), we can resist anger; to the extent that we have covered over the hurt with someone else’s idea of purpose and necessity (I’m doing this because I’m supposed to) – then there is anger that remains hidden.

There is a price of callousness to pay to believe that feeling anger cannot be allowed. It is hidden anger that can poison us. Repressed anger appears in displacement behaviors: one keeps it in at work, but can’t suppress it at home (or vice versa). One sucks up, but kicks down. One removes emotion from all interactions (intellectualization). Or one cannot tolerate expression of anger in a colleague or a patient: someone else’s anger reminds one of what cannot be tolerated in oneself. If you just suck up the hurt or the slight, and move on, you can feel in control and unaffected, a master of your fate. But that might make it more difficult to allow you to see and understand someone else’s struggles.

One way to find anger is to realize that it is probably present when we feel calloused or burned out. Take it out of its hiding place, and see what else comes with it. There is usually some of our own suffering in there along with the anger.

As tools and instruments of care, we must take care of ourselves. We can allow ourselves to feel anger: not to act on it, but to understand how we also suffer. Only after it has been examined, can we act with some wisdom – either to change ourselves and then model it, or to ask or call for change in others.

Let’s move on to also briefly touch on hidden anger in institutions and groups. How might an organization express its hidden anger, anger that interferes with the ability to provide care compassionately? I do not have a litmus test to prove it, or a prescription to eliminate it. But let us, as a starting place, assume that anger hides within institutions – there is the potential for it to poison relationships and obstruct empathy and compassion.

Change begins within individuals. Institutions are born of their leaders, so for our health care system to encourage compassionate care, our clinical and administrative leaders also have to seek out Delusion, Desire and Anger. These are great challenges for the leadership of any institution, and there needs to be support and appreciation for courageous and moral leadership.

Our leaders deal with changes all the time: those above you hold power and direct changes, and those below you, being human, resist the changes. The changes often involve losses of valuable beliefs and comfortable habits. Expectations will usually not coincide, and thus anger will be present. Hidden anger often appears as an attitude of “I don’t care to know” – as callousness. I hope that when policy and practice changes seem necessary, and anger starts to signal something is wrong, we can all look for delusions and desires that need changing, and the sense of loss that accompanies that. Hopefully with empathy and good communication, wise changes can be made and accepted. Let us always remember to include the wish to remain compassionate, not callous: to realize that we all suffer, and wish not to.

Institutional leadership has great responsibilities: payments, policies and politics challenge even the wisest leaders. The stakes are high. Rochester Regional Health is positioned to take advantage of resources created by forming an Accountable Care Organization. But there remains great uncertainty about how those resources will be distributed, and issues of payments, policies and politics will continue to make our leaders’ jobs difficult. (And now I have added a spiritual and ethical dimension that has not been discussed in management circles before!) Thank you to administrators for your anxieties and your best intentions. But please also, we kindly hope, examine your frustrations so that they do not block your own compassion.

As I have said now many times, I hope that the goals of the institution will not only include, but also prioritize awareness of suffering and encouragement of compassion. I also have three wishes to raise with our administrative leaders, which I believe could enhance our sense of shared community and purpose. They are changes for the future, and I believe they need to be considered as we continue to encourage compassionate care.

First, there is the meaningful enhancement of the electronic health record. It is our new fact of life, and there are many personal and institutional changes to be made to restore it to its proper role in patient care. I believe it is a part of being professional to know one’s patients as fully as possible and to communicate that knowledge so that others may know as well. I believe that improving the EHR will improve Patient Experience and Transitions of Care. Callousness to this issue would to me represent an example of institutional anger: disregard of the providers (let them fend for themselves) and disregard for the purposes and processes of patient care. The EHR is not only for billing and compliance.

Second, front line providers need emotional support and help with the frustrations of patient care. Patients are sicker and older, and there is a baby-boomer demographic bulge coming. We need help to maintain our compassionate selves, or we will burn out. The anger of an institution can produce clinicians who are automatons: efficient, productive, accurate, and cold. We are not that type of institution, but the elements are in place to create such a place. We need help to prevent the elements of burn-out: we need personal supports (encouragement and means to find and receive help and guidance); in our immediate work environment we need leadership and mechanisms that value and model communication over compliance; and we need systemic structure that not only communicates change effectively, but also seeks out ideas, recognizes dissent and describes vision.

Third and finally, administrators and front line clinicians have grown apart. We are fortunate to have administrators who were once good clinicians (and still are). But the worlds of management and patient care rarely speak the same language now or share the same assumptions about quality. They do not have many opportunities for dialogue and relationship. In an angry institution, the institution feels it knows best, and caring individuals can be sacrificed. It is so important for an effective health institution to find leaders with vision and kindness, not only managerial skills and loyalty. Health care administration has not reached its full maturity: it has borrowed from and been force-fed methods from industry that have not been adapted adequately. Good administration needs the help of effective clinicians to manage our unique challenge – not to create business, but to care for suffering.

These birds are doing their thing. This is almost other-worldly, a reminder that what we imagine to know still leaves much room for wonder and amazement. When I see this video, I marvel how it is possible for the birds never to crash into each other. And the answer seems to be: that they only respond to the birds next to them: they do not worry about the next flock, or the birds at the other side of the swarm. There is no room or time to think of their own needs – they only fly in relation to their neighbors, without regard for ideas, purpose, danger. If only we could do the same.

================================================================

So in this time we had together, I hope that I have interested you and challenged you with the idea that our work is not easy or routine, and can be made meaningful again when we remind ourselves why we are here. We are here as part of a long tradition of taking care of the elderly and the infirm, mostly without the technologies that now define modern medicine. The crux of our caring, the reasons we first committed to our professions, was to try to alleviate suffering. That is the role of compassion. We need to remind ourselves of that focus, even when we are struggling to manage our daily challenges.

Those impulses and motivations may seem idealistic, even romantic, after all we have learned, seen and done. To survive, we have had to become acculturated to the values of modern medicine, and in the process we have become calloused to the suffering. Callousness is understandable, but let us not allow it to become our norm or our goal. We need to remind ourselves that Delusion, Desire and Anger stand in the way of our compassion.

I have tried to point out that ultimately, we are connected and we are mortal. Our patients not only bring their suffering for healing and relief. They also bring reminders that we will follow them. We cannot serve them well if we are only looking at measurements and the bottom line. Health care requires empathy and compassion for patents – health care leadership can encourage compassion even while maintaining fiscal responsibility. Emphasizing compassion begins with each of us, but such change also needs institutional support.

It is frightening and saddening to be reminded that we will some day lose what we work for, have, and hope for. So we tend to grasp at and crave more cushioning and protection. But because we can change our minds and attitudes, I hope that we can build attachments to other than material and physical things. It is the work of a lifetime, to set examples. What changes can we initiate in ourselves in order to desire less and relate more? Maybe we can also want that what we stand for can be among our legacies.

Finally, we (individually and collectively) need to take care of each other and ourselves kindly and generously. In the Judeo-Christian tradition of loving neighbor as oneself, it is important therefore to know how to love oneself. It is important to be working on ourselves so that hidden anger from our losses and hurts (our suffering) does not prevent our being open to others. Let us acknowledge that anger lurks, and not let it be the poison that it can be. Let’s seek out and value anger because it tells us that change is needed. Sometimes it is internal change that is needed and sometimes it is external change. We cannot move forward in compassion unless we deal with the angers and hurts that isolate us from each other.

“The day is short and the work is endless. You are not required to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.”

Our work is to help those who suffer. Let us continue that work together.

Thank you.